The agricultural show season is in full flood and various Defra ministers have been invited to address breakfast meetings and answer questions. To add fuel to the debates, the House of Commons Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Committee published a report in early June, entitled “The future for food, farming and the environment”. As expected, the content, derived from six panels of witnesses who took as a basis the Defra consultation paper “Health and harmony: the future for food, farming and the environment in a green Brexit”, has generated considerable reaction. Not least from Professor Ian Bateman, director of the Land, Environment, Economics and Policy Institute at the University of Exeter. The Institute has been considering the future and a paper (“Public funding for public goods: A post-Brexit perspective on principles for agricultural policy”) is soon to be published.

There is considerable angst regarding the £3 billion that is paid out by the EU as farm subsidies. The general thrust is that the total payment will be maintained until 2022, although the allocation may be changed and a whole host of interested parties are looking to influence what happens next year and thereafter. The Institute paper highlights that three quarters of the fund is paid to one quarter of the farmers. An Agriculture Bill is due later this year and the House of Commons report refers to a new domestic settlement for England, which will help to deliver the government’s ambitions to “provide better support for farmers and land managers who maintain, restore, or create precious habitats for wildlife”.

Welfare considerations so far

There do not appear to be inputs from veterinary organisations within the House of Commons paper references. In January, the Secretary of State Michael Gove gave a speech at the National Farmers’ Union Conference and said that “investing in animal welfare is a clear public good”. He was quoted as saying that the government could support new industry-led initiatives to improve welfare standards.

John Fishwick (BVA President) responded that “it is essential that the UK’s post-Brexit agriculture policy recognises animal health and welfare as public goods”. At the Oxford Farming Conference, Michael Gove did not include animal welfare as a public good within his vision for post-Brexit agriculture. It seems important for this whole issue of farm animal welfare as a public good to be agreed and clarified.

Ian Bateman clearly indicates that farm animal welfare is a public good. However, he considers that paying farmers to ensure animal welfare is identical to paying farmers to avoid methods which fail to provide welfare. He adds that “if we pay farmers to avoid, in effect, animal cruelty then this is using public money to stop people doing something repugnant”. A further dilemma is that if a farmer treats the animals well, should a neighbour who fails to do so receive funding?

The way forward, the Institute proposes, is to apply regulations mandating against poor animal welfare and at the same time apply trade sanctions which restrict the import of food from those producers who cannot demonstrate that they apply animal welfare to the same standard. It is intended that such sanctions would control the undercutting on price of UK farmers, which should raise farm incomes.

The Institute paper indicates strongly that the direct delivery of environmental benefits is likely to be the major public good provided by farms and therefore should be the main focus of public subsidy. Support should be directed at

In January, the Secretary of State Michael Gove gave a speech at the National Farmers’ Union Conference and said that “investing in animal welfare is a clear public good”

an improvement in public goods and not increasing the private production of food. The House of Commons report indicates that public health could be improved through an expansion of some sectors of agriculture, but Professor Bateman is quoted as saying that “this is well meaning but misguided”.

The Institute emphasises that ensuring the poorest consumers have access to high quality food by subsidising food producers is at best highly inefficient and likely to be a complete waste of tax payers’ money. It is an important point that supporting food production and farmer profit is not seen as a public good and this is indicated within the House of Commons report. Ensuring standards within trade deals is seen as the way forward to achieving farmer viability.

Should farmers receive subsidy for good animal welfare?

The House of Commons report recognises that many farmers are dependent on subsidy payments. It is stated that direct payments can distort land prices, rents and other aspects of the market, creating a reliance on these payments, which can limit farmers’ ability to improve the profitability of their businesses. Defra advises that 42 percent of farms would be unprofitable if their direct payments were removed. Sheep, beef, dairy and cereal farmers are specifically highlighted as being dependent on subsidy.

Without an adequate replacement scheme, it is estimated that 25 percent of farms would be lost with a big impact on social cohesion, jobs, livelihoods, local food economy and ecosystem services. There are some 150,000 farms receiving subsidy. The provision of public good is criticised as being too simplistic and it is easy to see how the potential benefit to the public from a particular level of support can be favourably manipulated. Reports, papers and commentators are calling for hard definitions rather than generalities. There is certainly some difference of opinion as to the benefit, or otherwise, of recognising animal welfare as a public good. If UK farmers receive subsidy for animal welfare it may be more difficult to insist on the same welfare standards being applied to imports. However, if high welfare standards attract better returns on a commercial basis alone, this will require increasing levels of support from the industry, including a greater involvement of veterinary surgeons in knowledge transfer.

Setting the standards

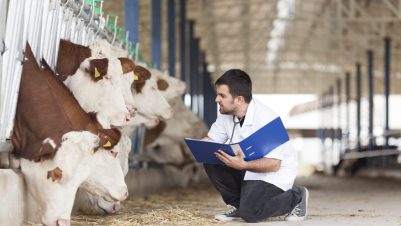

The difficulties of setting animal welfare standards have been raised at many veterinary meetings. The difference between animal neglect and cruelty and the relationship between welfare and profitability are well understood technically. For farm animal veterinary practices, the prevention of ill health is completely established, but defining the point of intervention can be problematic. The meat and milk buyers, with veterinary support, are directly influencing animal welfare by developing commercial and consumer awareness.

Many farmers need advice and education before welfare problems are ongoing that restrict profitability. It has been indicated that fewer cows with mobility issues and fewer coughing sheep enhance the livelihood of animals and give the public better confidence in ongoing animal care, but such outcomes may not satisfy “public good” as applied to replacement of EU subsidy.

It seems important at this time that the role of veterinary surgeons in maintaining and enhancing farm animal welfare is clearly understood by politicians, their advisors, economists and researchers.