Typically seen in giant breeds of dog, callus can be a simple condition to diagnose and manage. However, in cases with poor compliance, secondary infection (callus pyoderma) is common.

Callus

Callus is described as a localised hyperplastic skin reaction caused by pressure or friction (Hnilica and Patterson, 2017). It is a round to oval hyperkeratotic plaque that develops in sites overlying bony pressure points. The elbow is the commonest site followed by the hocks and, in those dogs with deep chests, the sternum (Miller et al., 2013).The problem is most often seen in giant breeds of dogs, including: Great Dane, St Bernard, Newfoundland and Irish Wolfhound. In these breeds, callus is most likely to occur on the elbow or hocks.

Callus may occur on the sternum in smaller breeds, such as:

- Dachshund

- Shetland Sheepdog

- Pointer

- Boxer

- Dobermann Pinscher

Diagnosis

In an uncomplicated case, the diagnosis is made on the history and physical examination, with a consideration of underlying causes. Possible underlying causes include:

- Dog continually favours a hard surface to lie on

- Inadequate soft bedding

- Obesity

- Hypothyroidism

- Extremely underweight/emaciation

- Orthopaedic problems causing pain enforcing constant rest

Treatment

In mild cases, observation alone should be sufficient. Soft bedding should be provided and protective dressings can be considered. It is important to identify and deal with underlying factors.

Prognosis

Provided that the underlying factors are dealt with and the dog will lie on soft bedding and/or tolerate supportive dressings, the outlook for a simple case of callus is fair to good. Compliance can, however, be difficult to attain, either with the dog or owner or with both.

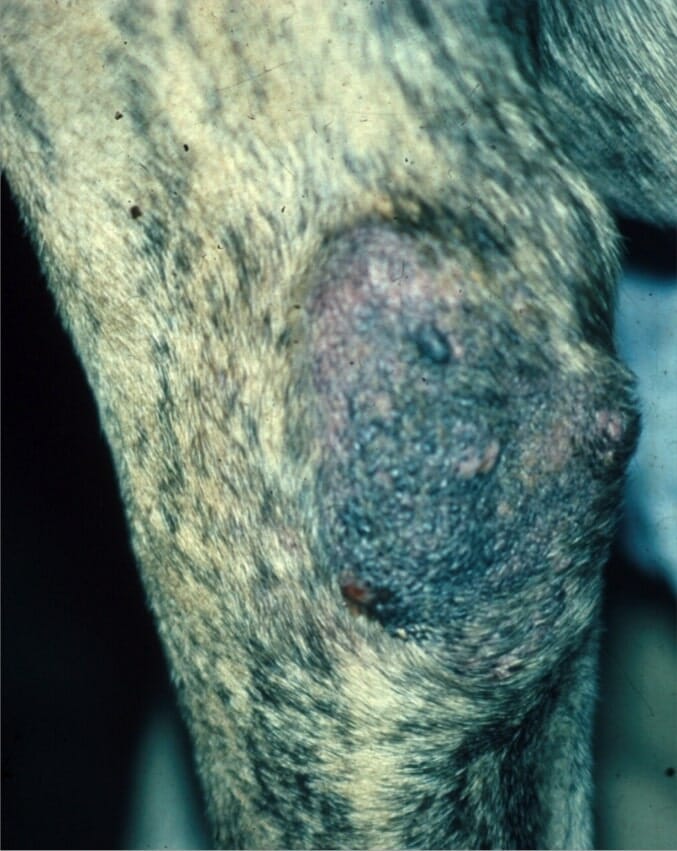

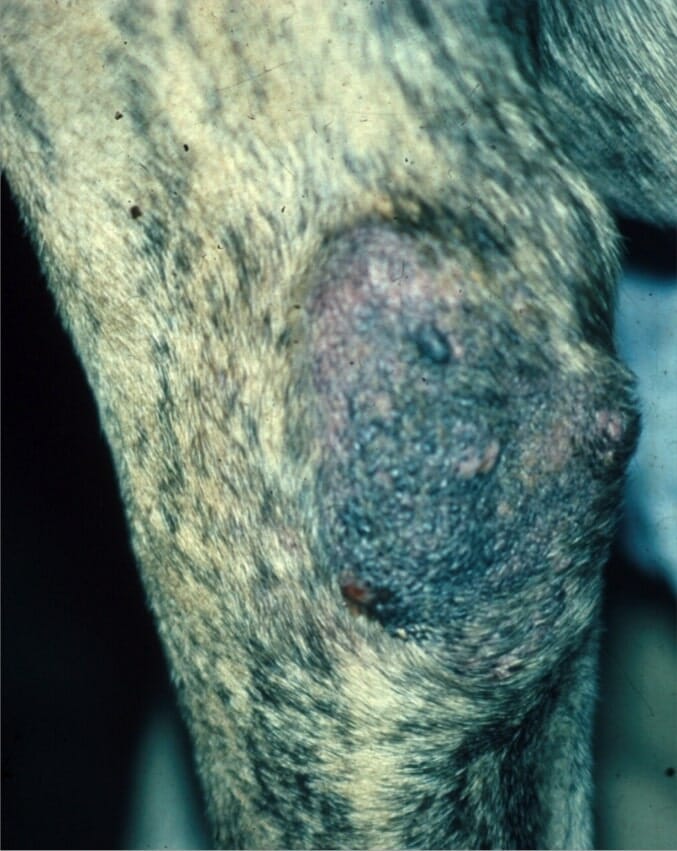

Callus pyoderma

In cases that are not managed effectively, and particularly when compliance is poor, secondary infection is common. In these cases, ulceration, fistulation and exudative discharges may occur, including the development of a deep pyoderma (Figures 1 and 2). In addition, and complicating matters, individual hair follicles may become impacted in the dermis, setting up a foreign body reaction. This increases the likelihood and severity of deep pyoderma.

The differential diagnosis in callus pyoderma includes:

- Dermatophytosis

- Demodicosis

- Other causes of deep pyoderma

- Neoplasia

- Decubital ulceration (Figure 3)

The same underlying causes for callus will need investigation.

Diagnosis

A full history and physical examination should be undertaken. Cytological examination should be performed. Assess for keratin debris (free hair shafts) and the presence of a purulent or pyogranulomatous inflammation with the presence of bacteria. Suitable techniques include impression smears and tape strips. Histopathological examination is rarely required and is best performed after control of bacterial infection. Typically there is epidermal hyperplasia, orthokeratotic/parakeratotic hyperkeratosis with follicular keratosis and dilated follicular cysts.

Treatment

- Attention to underlying factors

- Deep pyoderma will require long-term systemic antibacterial agents based on culture and sensitivity with cytological follow-up as owners’ assessments may be unreliable

- Topical therapy with chlorhexidine/miconazole in addition to systemic therapy. This may continue as a regular preventive treatment once the deep pyoderma is under control

- Whirlpool baths may be helpful

- Bedding and protective dressing as for callus

- Surgical intervention is not recommended as the common sequel of wound breakdown will intensify the problem

Prognosis

The prognosis is guarded to fair. The main difficulty is ensuring that the dog does not seek out hard surfaces to lie on and/or when the dog does not tolerate dressings. Very good communication with the owner is necessary and these cases could benefit from a home visit to check that environmental factors are as controlled as possible.

-1628179421-401x226.jpg)