Seemingly straightforward and simple, feathers are without doubt integral to defining a bird. A feather is a unique feature of birds that no other lineage possesses; however, despite this, they are often an overlooked area of importance within veterinary care, which can have serious negative consequences. Without feathers, a bird’s health is compromised, as is their ability to naturally express behaviours.

The purpose of feathers in birds

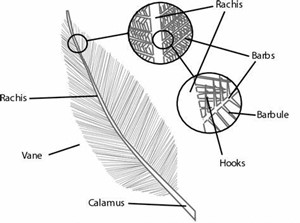

Feathers are composed of beta-keratin and are diversified for a variety of functions, but their original reason for evolution is believed to be for insulation. Despite their variety of forms, they are arranged within the same overall branching pattern (Sullivan et al., 2017). The generalised structure is as follows:

- The calamus is the hollow base of a feather, which extends into the central rigid fixed rachis, from which barbs emerge (Figure 1)

- Barbs are the main branches from the central shaft upon which barbules attach and which interlock with their neighbours, thus creating a feather (Phillipsen, 2020; Thompson, 2014)

Feathers for insulation

Some feathers have a loose, non-interlocking structure, which gives them a “fluffier” look and are known as plumulaceous feathers. This, alongside the longer barbules, results in air being trapped against the bird’s skin, acting as an insulation agent. This is seen in downy feathers. These feathers keep birds insulated against the cold (Phillipsen, 2020). Birds largely possess comparatively thin skin and lose heat quickly from their bodies. A “fluffed” patient is likely trying to stay warm, and if they present in practice like this, there is likely something negative occurring with their health, requiring extra effort to maintain internal temperature control.

Flight feathers

A bird prevented from expressing its natural behaviours, ie of those species which fly, is likely to have its welfare negatively impacted

Other feathers are “rigid” in structure, largely flat and possess interlocking barbules to form a barrier. This is commonly seen in flight feathers. In the author’s opinion, a bird prevented from expressing its natural behaviours, ie of those species which fly, is likely to have its welfare negatively impacted.

While not necessarily as important within captive pet species such as psittacines, flight feathers are undoubtedly important to maintain, especially for individuals in free flight shows, for example. Birds of prey, for instance, are much more likely to be either a “working” bird or a display bird, and as such require their flight feathers to perform their evolved functions well. If their flight feathers are damaged, in the worst case an individual is simply unable to fly until these have moulted through, which may have direct negative impacts on their owners. Ultimately, care and consideration is needed when handling any bird to ensure any potential damage is negated. Appropriate tools, such as a falconry glove for a bird of prey or a towel for casting, together with a competent handler are integral to this.

Display feathers

Display feathers evolved for a specific function entirely beyond essential needs; they are largely to attract a mate or for intimidation, be it of rivals or predators.

Assessing the health of birds in practice

Within practice, birds often present at times of sickness rather than health; therefore, being able to assess feathers effectively is part of good practice. Assessments are largely visual, in that you are looking for vibrant/shiny coloration, free from detritus, with a preened consistency (ie the feathers look well maintained). The feather itself should be flushed and non-barbuled, which otherwise may indicate sickness, compromised feather growth or patient interference (Figure 2).

It is worth remembering birds have evolved feathers for a reason, and without them, the reason for their evolution has been impacted. Birds’ feathers are so specialised that different feathers perform different functions and understanding which feather impacts which behaviour is important.

Impact of poor feather condition by species

For falconry species, the direct impact is perhaps more obvious. These are largely working or display birds, with comparatively few kept as pets where feather health isn’t such a consideration. To perform to the highest standards, birds of prey require near-perfect feather condition to maintain their evolved functions. Damaged feathers may prevent individuals from being able to fly effectively, which has a direct negative impact on their function. Feather issues within falconry are varied, but even a simple mishandling may result in a damaged primary that can have larger impacts than it may seem. Indeed, a bird may require a moult before it can fully function, effectively wasting a “season”.

Feather plucking behaviour

In more mainstream pet birds, psittacines are perhaps the most popular choice, while increasing numbers of private owners are maintaining poultry. Within households, psittacines may not have the option to express their ability to fly to full capacity, and as such, flight feathers may not be deemed so important to them. This, however, is a grossly inaccurate thought process as it can lead to the acceptance of more serious behavioural concerns, such as feather destructive behaviours (Figure 3). Indeed, under the Animal Welfare Act, the ability of an animal to express normal behaviours is of great importance, and this should be remembered at all times for such cases.

Reasons for feather plucking differ but largely follow one of three causations:

- Environmental: including poor housing, stimuli and diet

- Medical: including plucking from a painful area, or disease-related such as psittacine beak and feather disease

- Behavioural: including in response to a sudden change in the environmental set-up or loss of their companions or human bonds

Prolonged stress is a key element of feather-destructive behaviour. Providing a stable, safe and well-rounded diet within an enriching environment is essential. Behavioural steps such as exposing younger birds to differing situations before maturity can help minimise the risk of plucking in the long run when new negative stimuli do occur. Should feather plucking occur, then short-term collaring may be required to prevent further damage. Additionally, medical interventions such as clomipramine hydrochloride should also be considered.

Conclusion

Feathers are highly adapted, efficient and essential to birds; as such, they should be viewed as a wider extension of the individual animal themselves. Overall, a bird with poor feather status results in a bird with impacted health and welfare, and considerations should be reviewed regarding the quality of life for that bird. However, this is species-dependent, so it is important for veterinary professionals to be aware of the behaviours of different species, as well as the different roles of feathers in each species, to ensure good healthcare.