The concept of a “balanced diet” is frequently used in both human and veterinary nutrition to describe an ideal nutritional intake that meets all dietary needs. While this term might seem useful at first glance, it is often misleading when applied to the dietary formulation for companion animals.

The main objective of this article is to evaluate the importance of correct dietary formulation for animal health and welfare. The article aims to help the reader develop a better understanding of the challenges of the phrase “balanced diet” and how an animal’s diet should be better described to ensure focus remains on species-appropriate nutrition.

What’s wrong with the phrase “balanced diet”?

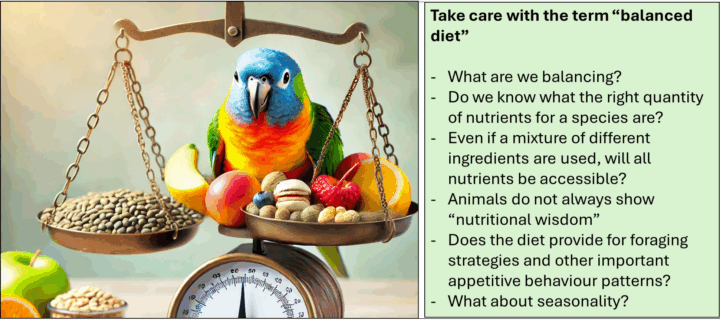

The phrase “balanced diet” can create confusion for pet owners and even veterinary professionals by oversimplifying the complex and species-specific nutritional requirements of different animals. The term can also be misleading when referring to feeding animals because it suggests a static or one-size-fits-all approach is always appropriate (Figure 1).

An animal’s nutritional needs vary based on factors such as age, health status, activity level and life stage (eg growth, pregnancy, lactation or senescence). The physiological changes that occur as an individual grows, develops and declines in later life need to be factored into dietetics and feeding regimes. We may also reach for the phrase “complete diet”, but this too may not provide the stimulation that comes from promoting natural foraging actions.

The phrase ‘balanced diet’ can create confusion for pet owners and even veterinary professionals by oversimplifying the complex and species-specific nutritional requirements of different animals

Instead, a more precise and scientifically grounded approach should focus on “species-appropriate nutrition”. This is not an article promoting raw meat feeding of dogs and cats as the sole way that these species should be fed. Yes, both are carnivores (the dog facultative, the cat obligate), but they have been through several domestication events that have resulted in the anatomy and physiology of the animal we see today (Grimm, 2016a, 2016b). Alongside individual animal needs, this should be a consideration in how, when and what to feed.

A one-size-fits-all approach

The main problem with the term “balanced diet” is that it implies a universally applicable, one-size-fits-all nutritional framework. This is often an oversimplification that can lead to restrictive or unsustainable eating patterns, neglecting the importance of individual needs and preferences. The lack of specificity with the term does not offer concrete guidance on what constitutes a healthy eating pattern, making it difficult for pet owners to understand and implement.

Any focus on individual meals rather than an overall pattern of feeding can lead to the misconception that every meal needs to be perfectly balanced, rather than focusing on a healthy eating pattern over time (how will animals accumulate the right nutrients they need if some foods – for example, hay for rabbits – is available ad lib?). The term inadvertently creates a binary view of food, leading to the idea that certain foods are inherently “bad” and should be avoided, which can be restrictive and unsustainable and reduce opportunities for nutritional enrichment that promotes behavioural diversity.

The term inadvertently creates a binary view of food, leading to the idea that certain foods are inherently ‘bad’ and should be avoided, which can be restrictive and unsustainable

If we promote a one-size-fits-all approach, we do not consider individual differences in nutritional requirements over life stages. A balanced meal must contain all required nutrients in precise proportions, which is neither necessary nor natural. In the wild, animals will consume a variety of foods over time that collectively fulfil their nutritional requirements – dietary needs are therefore met over days or even weeks rather than in a single meal.

What should we encourage instead?

Replicating natural feeding behaviours

Rather than striving for a concept of balance, pet owners and veterinary surgeons should focus on species-appropriate diets. This means understanding and replicating the natural feeding behaviours and dietary composition of each species. For example, domestic rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus domesticus) require a diet rich in fibre, primarily from hay, to maintain gut motility and dental health (Yeates and Bauman, 2019). Many commercially available rabbit diets (ie muesli-style food) contain excess cereals and grains that do not support their digestive physiology or provide opportunities for chewing and the production of caecotrophs. Rabbit owners should prioritise high-fibre forage and suitable fresh greens (eg parsley and basil) while minimising processed feeds to keep their rabbits healthy.

In addition to focusing on species-appropriate foods, feeding schedules should also reflect natural feeding behaviours. The “balanced diet” concept often leads owners to believe that pets must eat the same formulated food at the same time every day, but this is not how animals naturally consume food. Such a meal-based way of feeding means animals that naturally “trickle feed” will suddenly consume a large amount of energy or carbohydrate in one sitting and this has two effects:

- Disruption to physiology caused by the sudden ingestion of energy and nutrients

- A reduced diversity of behaviour because of the limited opportunities to perform foraging activities

Obligate carnivores, such as cats, will naturally consume several small meals throughout the day, reflecting their hunting patterns and success in hunting. Free-feeding kibble is not an appropriate substitute, as it often leads to obesity and metabolic disorders that require veterinary attention. Dogs, as facultative carnivores, are more adaptable in how and when they eat, so an intermittent fasting and rotational feeding system can really benefit their health and welfare. Feeding varied meals and occasionally incorporating fasts can promote metabolic health.

Herbivorous species should not be fasted or food-restricted. Rabbits, for example, need continuous access to hay as this is crucial to mimic their natural grazing and browsing habits, while preventing gastrointestinal stasis and ensuring correct and even tooth wear. Rabbits fed a meal-like schedule (such as that used for a pet dog) will not experience positive welfare outputs – even if the diet fed is “balanced”.

A more holistic and flexible approach to companion and domestic animal nutrition can be focused around:

- Understanding species-specific needs and avoiding inappropriate foods

- Prioritising fresh, whole foods over highly processed diets when available, possible and suitable

- Allowing for dietary variety over time instead of forcing rigid meals that are considered “complete”

- Tailoring feeding schedules to mimic natural eating patterns when this has been shown to promote welfare in that specific species

- Thinking about palatability, seasonality and changes in nutritional requirements across season

- Always considering individual health conditions and life stages, adjusting diets accordingly to ensure food can be effectively processed and consumed

Take nutritional wisdom into account

Considering nutritional wisdom is also important. Nutritional wisdom refers to the ability of animals to select a diet that meets their nutritional needs based on instinct, learned behaviours and internal cues such as taste and hunger (Brunstrom and Schatzker, 2022). In theory, animals have evolved to recognise and consume foods that provide essential nutrients while avoiding harmful or nutritionally poor items. This concept has been observed in animals under human care and those in the wild, where they may show preferences for foods that help correct nutrient deficiencies or maintain overall health.

However, animals do not always display perfect nutritional wisdom (Forbes and Kyriazakis, 1995). Factors such as the availability of processed foods, a cafeteria-style feeding schedule (where animals have multiple options to select from) and learned behaviours can override more instinctive food choices. For example, domestic livestock can show strong preferences for high-calorie, palatable foods (Provenza, 1995), even if they lack essential nutrients, much like humans who crave junk food.

Understanding how a species searches for, and locates, food, and the associated behaviour patterns around this, helps ground species’ appropriate diets in evidence of their needs

In some cases, animals may not have evolved to recognise modern, commercially available diets, leading them to consume more of one foodstuff compared to another. A lack of nutritional wisdom means species may not consume a complete “balanced diet” even if one attempts to provide this for them. Understanding how a species searches for, and locates, food, and the associated behaviour patterns around this, helps ground species’ appropriate diets in evidence of their needs.

Encouraging appetitive behaviour

The term “appetitive behaviour” refers to the active, goal-directed actions animals perform to locate and obtain food before consumption (Dixon et al., 2014). These behaviours include searching, hunting, scavenging or manipulating objects to access food, and they are driven by internal and environmental cues. Appetitive behaviours are flexible and adaptable, allowing animals to modify their approach based on food availability and past successes, ensuring they efficiently meet their nutritional needs.

Appetitive behaviours are associated with specific motivational states and, therefore, how diet is provided (and when) needs to be considered to ensure the animal is physically satiated (ie after consumption of the food) and psychologically satiated (ie from performing the relevant actions associated with feeding and foraging). A behaviour chain consists of different actions that link together, with the preceding one stimulating the following.

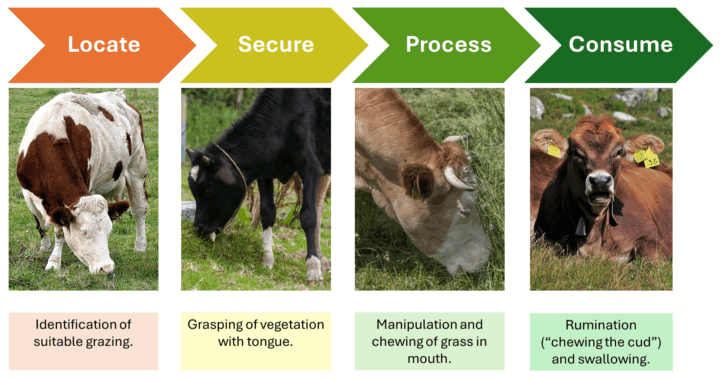

Figure 2 shows an example of a foraging behaviour chain in domestic cattle (Bos taurus) that is, in itself, appetitive in nature. It shows how a cow’s anatomy, physiology and morphology all work together to perform a behaviour change that is appetitive in nature and ultimately satiates the individual. Various sensory modalities are used to locate food (ie suitable grass for grazing), which is then secured with the cow’s flexible and muscular tongue. The cow’s dentition, dental pad and tongue all help process the grass, which is ground up by a rhythmic chewing motion and then swallowed. The cow consumes and regurgitates (rumination) the grass as the final act of this behaviour chain. When fed a “balanced diet” of concentrate ration (ie pellet), there are limited opportunities for being satiated because this behaviour chain may not be fully performed.

Sometimes we can compromise between complete feeding regimes and consider behaviour and opportunities for eating a range of ingredients

Sometimes we can compromise between complete feeding regimes and consider behaviour and opportunities for eating a range of ingredients. For example, mixing forage and concentrates together in a total mixed ration (TMR) (Figure 3) maximises opportunities for trickle feeding (important concentrate pellets are harder to find and have to be sorted from the hay and forage element), slows the ingestion rate of the cow (which benefits the animal’s gastrointestinal health) and limits the options for the animals to overconsume one dietary ingredient and then not consume another equally important element of their food. Perhaps there is some degree of “balance” to TMR as a diet (Schingoethe, 2017), so a pragmatic approach to what we need to provide and how best to deliver this from a welfare and health perspective is also required. Either way, this shows how a species-appropriate diet can be formulated alongside digestive physiology.

Final thoughts

Overall, the term “balanced diet” is an unhelpful oversimplification when formulating nutrition for companion animals and domesticated species. It encourages a rigid, processed-food-centric approach that may not align with an animal’s natural dietary needs. By focusing instead on species-appropriate nutrition and feeding schedules, pet owners and veterinary professionals can ensure that animals receive the best possible diet for the individual across life stages. Rather than seeking balance in every meal, the goal should be to provide a diet that meets physiological needs over time, using the best ingredients available.

| Questions for discussion: 1. What evidence is available for the creation of species-appropriate diets for species commonly housed as domestic pets and companion animals? 2. Is this evidence up to date, relevant, modern and based on empirical data? 3. How can clients, owners and caregivers be best educated in new terminology and new ways of describing animal nutrition that can embed good welfare as a core of pet or companion animal care? |