Talking to cattle veterinary surgeons about the past few months, the repeated phrase is that they consider themselves lucky compared to other sections of the profession. The observations and comments are personal to particular situations and do not include financial impacts on a business, that will need to be assessed later. With the introduction of lockdown and the new order of working it is emphasised by all that there was an initial period of change and adaptation but that the new routines that were developed have not only enabled animal welfare and farm management to continue, but in many cases the enforced changes have shown improvements that will be ongoing.

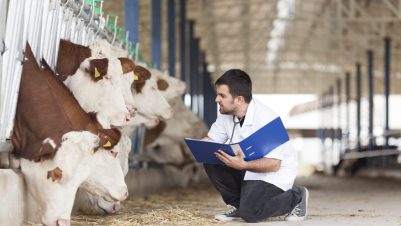

One of the early areas of difficulty and concern was maintaining a two-metre distance with TB testing (Figure 1). A few key phrases from the Veterinary Record in April indicate some of the angst in interpreting the directives: “the risk of infection is as much from our clients to our vets as it is from our vets to our clients”; “it is not acceptable for, often young, OVs to be pressurised into testing cattle that require manual restraint”; “all of us would put human health and safety above any animal disease control, notifiable or not” (Biggs, 2020).

Vets, having put the question to farmers about how they can manage protected testing, found that many clients responded very positively and found practical ways of overcoming disease transfer risks, particularly with handling calves. A general observation is that farmers were unruffled and simply expected the vet to get on with the job, and that this resilience is admirable and may be a reflection of farmers having experienced foot and mouth and bovine spongiform encephalopathy. Farmers are said to be “quite good at isolation” and lockdown left them somewhat bemused and commenting “welcome to our world”.

It is also a general finding that, creditably, vets and practice staff all simply adapted to the work requested at the time. Non-essential work initially included training and herd health. Veterinary consultancy appears to have been a major casualty with cancellations of overseas trips and gatherings of vets, farmers and industry. The situation was described as “glum”. Having had diaries “wiped out” with lockdown, there has been considerable development and adaptation, but although technology has helped, it will take time for disease control programme modules to catch up. Getting initiatives operating effectively is described as “such hard work” but now that the social distancing requirement is likely to operate for many months, if not years, the effort is expected to lead to more targeted and effective means of delivery. Reduced travelling has meant that more allocation has been available for “thinking time” and significant changes can be anticipated in content as well as means of delivery. Time available to take stock is seen as a positive outcome.

It is clear that cattle practices have taken action to protect vulnerable members of staff. In some cases this has meant furloughing, but for all practices working from home is a reality. Not allowing vets to come into the practice premises at the end of the day is highlighted as one of the downsides. Considerable efforts are moving ahead to reinstate the social interaction between practice members without putting individuals at risk. Also emphasised is the need to not put the practice at risk. Self-isolation for two weeks is manageable for the practice when it only affects one individual, but if several vets and support staff are involved, the impact on day-to-day administration is considered too great. The use of Zoom within a practice is a reality that is being enhanced and developed. Not everyone finds online conversations particularly satisfying but, for now, that is the way to prevent working in complete isolation.

Farmer clients are advised not to enter the veterinary premises. Medicines are dispensed in various ways, with a collection point and delivery by the vet common options. Visits by reps and others have not taken place and video conferencing sessions have allowed planned discussions, which individual vets have found beneficial, with targeted outcomes. During March, practices saw an increased uptake of medicines by farmers, a reflection of the uncertainty of supply, but this soon settled down. The spring saw difficulties with milk buyers encouraging reduced supply, due to the reduced catering uptake of liquid and cream. Dairy farmers are often experiencing milk buyer-led difficulties, over supply and price, but they are genuine threats to management. Stability appears to have returned for many producers, until the next alarm.

It is inaccurate to generalise, but there appears to be a forward-looking idea that “there are no plans to lay off cattle vets because of COVID”. It is somewhat heartening to learn that Synergy Farm Health has recently introduced two new graduate interns. It may be that the class of 2020 will consider cattle medicine a viable option for their skills. All agree that ways of working have changed, are undergoing continual development and cattle practices are preparing for the long term. It is recognised that there is some weariness within the working teams as the busy winter period approaches and that COVID has changed the work/ home balance.

Remote vetting is described as a transformation. Initially, vets and clients were “forced to Zoom” but more focused meetings have now arisen. More virtual meetings about prevention and online modules are seen as increasingly convenient for delegates, although less so for the trainers. On a one-to-one basis there has been effective talking with colleagues and with clients. One practice indicates specifically that discussion groups with beef and sheep farmers have worked, with online interaction and exchanges between the delegates and with the vet presenting being effective. A survey of 387 English and Irish farmers in May (Boehringer FarmComm 2020) indicated that some 70 percent of farmers would take part in social media and online meetings. That figure is likely to be greater now. The company has stated an intention to support vets who want to be proactive in engaging with their farmers whatever the COVID restrictions.

Farm assurance and herd health became restricted between vets and clients initially but this has now been overcome. When initially introduced, the programmes were not enthusiastically embraced by some farmers and were seen as outside interference. The COVID restrictions appear to have been used by a minority as an excuse not to fully engage. Practices recognise that non-engaging clients are a challenge. However, in response to the specific question of whether individual vets feel that animal welfare has been compromised and an upsurge in disease can be anticipated, the view is that enough has been done to prevent undue problems in the coming months.

One of the areas that directly challenges dairy herd viability is foot health. Initially, the view was that lame cows can wait a week or two but that no number of lame cows can justify the loss of one human being. It seems that foot trimmers have been able to carry on working in a socially distanced manner with minimal human contact. Fortunately, the length of the cow has allowed social distancing for veterinary treatment. Mobility scoring will be able to be continued. There are indications that the thinking time benefit will directly enhance the delivery of healthy feet programmes in the future.

One of the points about luck is the recognition that cattle vets are able to work in the fresh air with space and applied hygiene. There are dangers and analysing risk is now the norm with formal assessments carried out for each clinical and advisory situation. The veterinary practice risk assessor is now an indispensable member of the team.

Grateful thanks for their personal observations from Owen Atkinson, Andrew Biggs, Nick Bell, Paddy Gordon, Jon Reader and Matt Yarnall.