The presentation of a non-limb, “unblockable” forelimb lameness has been recognised in the horse for many years, with a proportion of these cases considered likely due to pathology of the caudal cervical vertebrae (Ricardi and Dyson, 1993; Dyson and Rasotto, 2016; Dyson, 2020). The more recent ability to perform computed tomography (CT) of the entire neck of the horse has enabled a better understanding of how neck issues can cause lameness via cervical spinal nerve impingement, also known as radiculopathy.

It is becoming clear that cervical spinal nerve impingement causes a range of signs and symptoms in addition to obscure thoracic limb lameness. Work is actively ongoing to help gain a better understanding of the aetiology, pain mechanisms, diagnosis and treatment. Literature on this topic is still scarce, and this article is based on current published knowledge alongside the author’s learnings from case experience, surgical caseload and collaboration with other veterinarians with an interest in this field.

Anatomical guide to the cervical spine

The cervical portion of the vertebral column consists of seven vertebrae (C1 to C7), linking the skull and the first thoracic vertebra. There are three articulations between each vertebra; the intercentral joint articulates between the vertebral bodies via the intervertebral disc, and a pair of large articular process joints (APJs) articulate between the articular processes, which are located dorsolateral to the vertebral bodies and spinal canal.

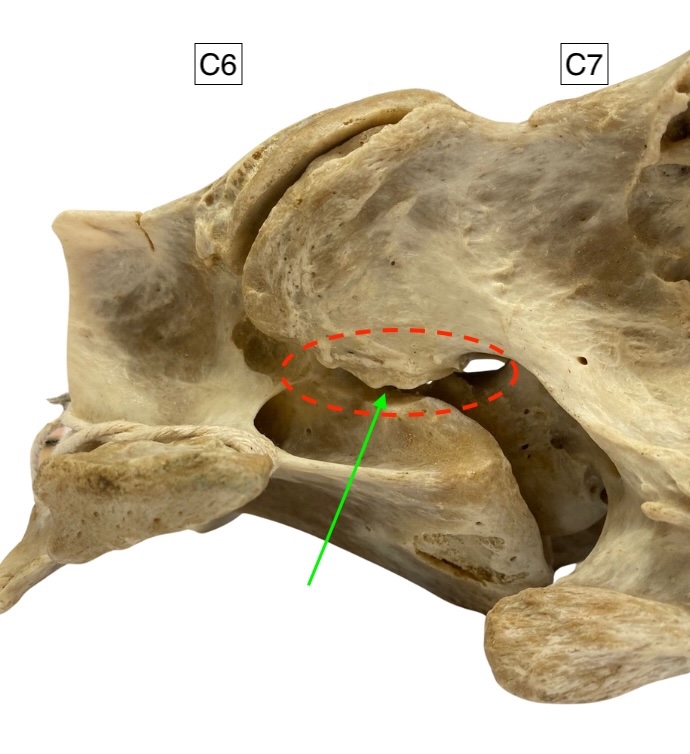

The APJs are cartilage-lined synovial joints contained by a distensible joint capsule. They have an important role in the biomechanical function of the neck. Eight paired spinal nerves innervate the neck and cranial thorax. The first pair emerges through the lateral foramina of C1 (the atlas), and the second to eighth cervical spinal nerves emerge sequentially through the intervertebral foramina between each vertebra. The eighth nerve exits between the seventh cervical and first thoracic vertebrae. Additionally, the fifth to eighth spinal nerves contribute to the brachial plexus (Dellmann and McClure, 1975). The foramina are located between the intercentral joint ventrally and articular process joints dorsolaterally (Figure 1) and contain the dorsal and ventral rami of a spinal nerve, as well as blood vessels and connective tissues.

Understanding cervical radiculopathy

Cervical radicular pain is perceived in the neck and/or thoracic limb, caused by irritation or compression of a cervical spinal nerve and/or nerve roots (Lyer and Kim, 2016). The close association of the intervertebral foramen to the articulations of the neck makes it susceptible to narrowing caused by articular pathology. In the horse, this is most commonly caused by osteoarthritic changes of the articular process joints. It may also rarely be caused by impingement due to intercentral disc pathology or intra-articular osteochondral loose bodies situated within the cranioventral outpouching of the APJ.

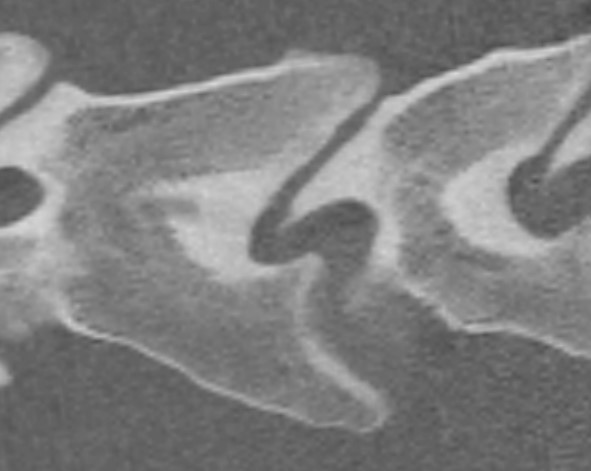

In severe cases of APJ enlargement, the ventral margin of the articular process can make contact with, or buttress, the opposing vertebral body, causing sclerosis, cyst-like lucencies and even fragmentation, all evident on CT imaging (Figure 2). Bone pain and reduction in neck mobility is additionally hypothesised in these cases. Foraminal dimensions in the horse have been shown to vary considerably with neck position, although the details are not yet understood. An ex vivo study in clinically normal horses demonstrated that only 20 degrees of dorsal neck extension caused greater than 50 percent reduction in height of the C6/C7 intervertebral foramen (Sleutjens et al., 2010), suggesting that extension of the caudal neck might exacerbate nerve impingement. Pathology affecting the APJs and intervertebral foramina appears most prevalent in Warmblood sport horses, often presenting between 6 and 12 years of age; however, any equid may be affected.

An ex vivo study in clinically normal horses demonstrated that only 20 degrees of dorsal neck extension caused greater than 50 percent reduction in height of the C6/C7 intervertebral foramen… suggesting that extension of the caudal neck might exacerbate nerve impingement

Clinical signs of cervical radiculopathy

Cervical radiculopathy is well recognised in humans, causing pain radiating into the arm, neck pain, tingling or numbness in the arm, and weakness of the hand. In horses, a combination of signs is noted and might include:

- Neck pain characterised by:

- Reduced neck mobility noted during “carrot stretches” or during movementLoss of neck musculature, including muscles of the shoulder and pectoral region. This may be due to reduced use or peripheral neuropathy

- Ipsilateral thoracic limb gait deficits such as:

- Reduced cranial phase to the stride

- Tripping

- Lameness, often described as a hopping or skipping gait

Lameness may be intermittent and variable in severity or may be consistently present under certain circumstances. It may be only evident when ridden and can be variable depending on head position and rein contact.

Reports of “behavioural issues” are common, now recognised to be a pain response and often found to be related to neck position

- “Ridden difficulties” are characterised by (Dyson, 2022):

- Reluctance to work

- Reduced performance

- Inability to reach a horse’s athletic potential

- Ridden ethogram signs of pain

A ridden assessment may reveal forelimb gait asymmetry, but also ethogram signs of pain (Figure 3). Reports of “behavioural issues” are common, now recognised to be a pain response and often found to be related to neck position: for example, a horse that will not load into a horsebox where its head is tied in an elevated position, or a horse that has lost confidence going cross country and struggles with drop fences. Note that expressions of pain are non-specific and may originate from a multitude of sources.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on a combination of relevant clinical findings, imaging evidence of reduced intervertebral foramina dimensions, ruling out differential diagnoses and a positive response to appropriate treatment. Many signs associated with radiculopathy are non-specific to the neck and other possible causes must be ruled out through careful clinical examination and investigation of other differential diagnoses. Commonly, this includes limb lameness, back pain, dental issues or equine gastric ulceration syndrome. It is important that lameness investigation (eg diagnostic analgesia and imaging) fails to localise lameness to the limb and that the horse is additionally assessed for hindlimb lameness, remembering that bilateral lameness may not be evident as a gradable gait asymmetry.

What constitutes a definitive or clinically significant reduction in foramen size is unknown and appears to be variable

CT is the only imaging modality able to fully assess the dimensions of the intervertebral foramina; however, radiographic or ultrasound findings of significant APJ enlargement increases the likelihood of there being foramen impingement. Oblique lateral radiographs aid the interpretation of APJ abnormalities and help reveal laterality when there is APJ asymmetry. Cervical radiographs of diagnostic quality can be difficult to obtain in the field and transport to a suitable facility for imaging might be appropriate. What constitutes a definitive or clinically significant reduction in foramen size is unknown and appears to be variable.

Treatment of spinal nerve impingement

Medical treatment

Systemic analgesia with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs) is anecdotally poorly effective, unless there is an articular pain component to the presentation. The efficacy of gabapentin as a treatment for radicular pain in horses is not known and oral bioavailability of this drug is known to be low (Terry et al., 2010). Ultrasound-guided intra-articular corticosteroid medication of the affected articular process joints can be beneficial, likely through improving joint comfort and reducing soft tissue expansion of the joint. Ultrasound-guided perineural corticosteroid medication of the ventral ramus of the spinal nerve has been described in cadavers in several studies, achieved in a similar fashion to APJ injection (Touzot-Jourde et al., 2020; Fouquet et al., 2022; Wood et al., 2021). The passage of the needle must be continuously visualised via ultrasound to maintain accuracy of injection and to avoid the vertebral vessels. A retrospective analysis of 47 perineural injections in 12 cases of radiculopathy observed clinical improvement in nine horses, with six returning to full work (Wood et al., 2025).

Surgical treatment

A minimally invasive surgery performed in humans has recently been translated to the equine field

A minimally invasive surgery performed in humans has recently been translated to the equine field, first described by Swagemakers et al. (2023). The procedure is rapidly gaining traction as a viable and effective treatment option in the horse and is now available in Europe, the United Kingdom and across the United States.

Under general anaesthesia, a specialised single portal endoscope system (Vertebris Stenosis, RIWO Spine, Knittlingen, Germany) is used to access and visualise the pathologic intervertebral foramen via a 15mm skin incision (Figure 4). Impinging bone is removed using a motorised burr. The procedure requires preoperative planning from CT imaging and is performed under careful radiographic and ultrasonographic control. Due to the minimally invasive nature of the procedure, morbidity is low and horses generally return to turn out and exercise in a short timeframe. Early experiences of the first 70 cases in Germany suggest a good prognosis following surgery, with appropriate case selection and rehabilitation being important factors (Swagemakers et al., 2023). Much is still unknown about the long-term clinical outcomes, but with over 300 horses having now undergone surgery worldwide, evidence is expected to emerge over time, hopefully along with increased depth of knowledge regarding surgical technique, optimal case selection and rehabilitation.

Conclusion

It is becoming increasingly clear that neck pain is an important differential diagnosis for poor performance in the horse. A forelimb lameness may originate from the caudal neck; however, this presentation is rare, and limb lameness must always be considered in the first instance. Cervical radiography is very useful, but unfortunately cannot reveal intervertebral foramen dimensions and therefore stenosis. Plain CT imaging of the entire neck can now readily be obtained at several referral centres across the UK, performed under a short general anaesthetic. Treatment options for radiculopathy are emerging, with nerve root medication and surgical widening of the foramen along with dedicated rehabilitation programmes showing promise.

| Discussion points: 1. What steps might you take to investigate a horse presented to you with a forelimb lameness that is only evident when the horse is ridden? 2. You decide you want to obtain a set of neck radiographs for your equine patient. How will you approach obtaining diagnostic quality images? |