Proliferations of cancer cells in or around the eye are not an unusual finding in cattle. However, ophthalmic neoplasms in cattle are much more prevalent in some parts of the world than in others. This article will discuss the main causes of ophthalmic neoplasms along with their risk factors and treatment.

Causes of ophthalmic neoplasms in cattle

The most common tumours that cause cancer in the eye and surrounding tissues in bovines are squamous cell carcinoma and lymphoma (also called lymphosarcoma).

Leukosis

In cattle, lymphoma – the uncontrolled proliferation of the lymphocytes that cause tumours – is caused by leukosis. There are two forms of leukosis: it can be either sporadic or caused by a virus called bovine leukosis virus. Sporadic bovine leukosis is a lymphoproliferative disease of unknown aetiology. It is possible that pathogens are involved in the development of this disease, but these have not currently been identified (Constable et al., 2016).

Bovine leukosis virus causes a disease called enzootic bovine leukosis (EBL). This is a notifiable disease in the United Kingdom, but it has not been diagnosed in Great Britain since 1996 (APHA, 2018). EBL is traditionally monitored and eradicated using serology. Great Britain eradicated this disease by screening blood samples that were primarily taken for brucellosis serology in the 1990s. Most Western European countries have also run eradication programmes and are currently free of EBL. A few other countries outside Europe have recently run eradication programmes and managed to eradicate or lower the prevalence of the virus significantly (eg New Zealand). This situation is in stark contrast to some other countries (eg the Americas), where the seroprevalence at herd level can be 80 to 90 percent (Lv et al., 2024).

Risk factors for leukosis in cattle

Generally, dairy herds are much more commonly infected by bovine leukosis virus than beef herds. The incidence of clinical lymphosarcoma is also much higher in dairy herds than beef herds. Saying that, infection with EBL does not mean that the animal will develop tumours per se. Incidence studies have shown that in countries where the virus is present, the occurrence of clinical lymphosarcoma is estimated to be 1 per 1,000 per year. In infection-free countries, clinical cases are estimated to be 1 per 50,000 (Constable et al., 2016).

Incidence studies have shown that in countries where the virus is present, the occurrence of clinical lymphosarcoma is estimated to be 1 per 1,000 per year

Studies have, however, shown that genetic resistance is the main reason why infected animals do not progress to clinical disease. It does seem that genetically selected high-producing dairy cows can be more susceptible to clinical disease compared to dairy cows that are bred for lower production. This means that in high-merit herds, an annual mortality rate of 2 to 5 percent is not uncommon in dairy herds with a high seroprevalence (Constable et al., 2016).

Treatment and management options for leukosis in cattle

Clinical leukosis can cause clinically detectable lesions in the periorbital tissues, which in turn can cause exophthalmos (protrusion of the eyeball). This is not a very common presentation but does happen in a small percentage of leukosis cases. This clinical sign can also occur bilaterally, along with generalised lymphadenopathy (Constable et al., 2016).

As EBL is a notifiable disease, all animals that test positive need to be destroyed. There is no treatment available for food-producing animals with sporadic leukosis.

Ocular squamous cell carcinoma

Ocular squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) is the most commonly occurring eye tumour in cattle and one of the most common of all neoplasms encountered in this species (Constable et al., 2016). The common term for ocular squamous cell carcinoma is “cancer eye”.

Risk factors for OSCC in cattle

As OSCC is so common and much more prevalent in certain parts of the cattle population, a large amount of research has been carried out to identify risk factors and more susceptible animals in the population. Development of the malignant tumours has been linked to several risk factors. This article will discuss the two factors that contribute to most of the cases.

- Ultraviolet (UV) light – cattle exposed to high levels of UV light are a lot more susceptible to cancer eye (Tsujita and Plummer, 2010). In sunnier climates, especially in places with lots of sunshine at higher altitude, the incidence of the disease increases dramatically. This happens because UV light damages the DNA of skin and periorbital tissues, which results in processes that can cause the development and proliferation of cancerous cells. This process also occurs in other mammals, such as humans

- Breed – quite a few cattle breeds are more susceptible to OSCC, but Herefords (and their crosses) and Holstein cattle are the most commonly affected. This has two reasons. Firstly, the skin, mucosa and other tissue on and around the eye globe is a lot more susceptible to OSCC if there is no pigmentation. The presence of melanin (or pigmentation) in these tissues has shown to have a protective effect against OSCC. As Herefords and their crosses have white heads, their eyelids and other periorbital tissues lack pigmentation. OSCC is also more prevalent in Holsteins with white heads than black ones. Secondly, research has shown that there is also a factor of hereditability within these breeds: cattle born of animals affected were much more likely to develop the tumour than the progeny of unaffected bovines. This effect is even clearly seen with only the dam or the sire affected (Tsujita and Plummer, 2010)

OSCC tumour proliferation

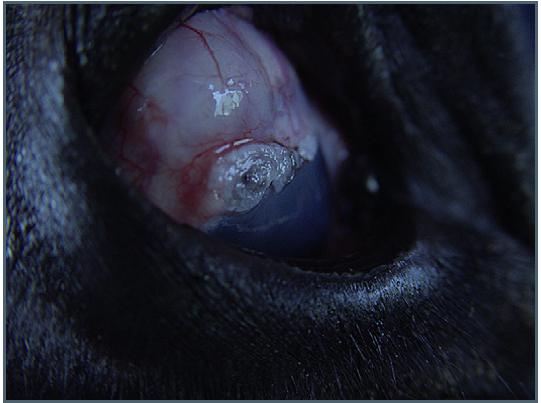

Most bovine OSCCs develop on either the lateral conjunctiva or limbus; the lower eyelid, third eyelid and medial canthus are less commonly affected areas (Tsujita and Plummer, 2010) (Figure 1). The limbus is the area of the eye where the translucent cornea meets the white sclera. Classic OSCC lesions are similar to a papilloma but are more destructive of the surrounding tissues. The base is wide, and the middle can be necrotic and can produce pus.

Lesions develop in four stages. Firstly, a plaque (circumscribable area) occurs, which is followed by a keratoma (a hardened, thickened piece of tissue). A papilloma (benign tumour) then develops. These three precursor stages are all benign and often regress spontaneously. However, the final evolution that follows these precursor stages is the development of a squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). (SCCs can be preceded by any of these three precursor stages.) Unlike the benign precursor stages, OSCCs are invasive and do not regress.

These malignant tumours can metastasise along draining lymph nodes into the cervical lymph nodes, but this only takes place later in the course of the disease. Clinically, this means that for a favourable prognosis it is important not to leave the tumour grow too large. Bovines do not tend to develop resistance to the tumours; few cows have been found with circulating antibodies for OSCC. Also, the tumours produce immunosuppressive substances, which means OSCCs will often grow continuously if not treated (Constable et al., 2016).

The tumours produce immunosuppressive substances, which means OSCCs will often grow continuously if not treated

The precursor stages of OSCC tend to be less than 2cm in size. Any lesions larger than this are generally squamous cell carcinomas. This means overtreatment can occur when the farmer is very vigilant of the condition. Differentiating benign precursor lesions and malignant carcinomas can be carried out by clinical assessment and cytology (Constable et al., 2016).

Treatment of ocular squamous cell carcinoma

Treatment of OSCC consists of removing the cancerous tumour. Larger tumours that invade the structures of the eye will mostly warrant enucleation (removal of the whole eye and its surrounding tissues). Smaller tumours can be removed safely with small margins (2 to 3mm).

In the latter case, the addition of cryosurgery/cryotherapy – the use of liquid nitrogen to freeze tissues – is preferred. Cancerous cells are more susceptible to freezing then non-cancerous cells, which means that this method is a good way to remove smaller or debulked lesions (Tsujita and Plummer, 2010). Cryotherapy also dulls the nerve endings for some time after treatment, which is an excellent method to reduce pain. Cryosurgery can be very effective in destroying superficial and some deeper cancerous cells in tissue. The best results have been obtained by two freeze–thaw cycles (Constable et al., 2016), wherein the lesions are frozen two consecutive times to avoid recurrence.

Cancerous cells are more susceptible to freezing then non-cancerous cells, which means that this method is a good way to remove smaller or debulked lesions

Recurrence occurs most commonly at the treated site or in the previously unaffected eye. To prevent recurrence, it is important to select cases for treatment carefully: as larger, more invasive masses can metastasise, culling can be indicated (instead of enucleation) if the OSCC is invasive and exceeds more than 5cm in diameter.

Final thoughts

On a final note, we must not forget to consider animal welfare when it comes to ocular neoplasms in cattle. Any mass in the eye region that causes pain and discomfort needs addressing accordingly. In that sense, it is not relevant if it is cancerous or not.

As a vet in clinical practice, it is important to understand the differential diagnoses of the different ophthalmic neoplasms, especially as it is sometimes warranted to inform the authorities of a cow with a neoplasm.

Over time, and with lots of practice, it becomes easier to give an accurate prognosis for a lesion, which is beneficial for the cow and the farmer.