The opening Western Counties Veterinary Association (WCVA) meeting of 2019 attracted a broad church of people to listen to Dick Sibley report on the findings of an alternative approach to the control of bovine tuberculosis (bTB) and discuss the way forward. A slightly more formal presentation had been delivered at the BCVA Congress meeting in October 2018, but this evening was more directed at working cattle vets in Devon.

Defra and APHA advisors, wildlife protectors, testing developers and Cymorth TB managers shared understanding with Devon-based farmer Robert Reed, who had engaged in an in-depth alteration to management of his cattle to reduce the financial and practical burden of bTB. The topic received lots of public interest, particularly thanks to the involvement of musician and TB activist Brian May, who explained his role in supporting farmers and vets to control bTB and protect badgers.

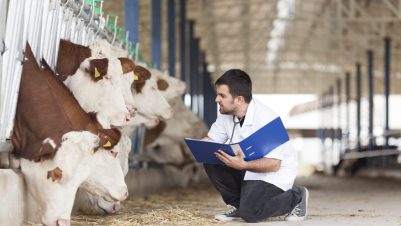

The TB control strategy, led by cattle vet Dick Sibley, involved the use of Actiphage to clear a dairy herd that had been suffering with TB since 2012. Measuring the presence of live bacteria in the blood was incorporated as a complementary method to other techniques. The method was claimed to enhance early detection and containment of the infected cattle.

It will be no surprise to cattle vets that the government has been very protective of TB policies over the years and reacted unfavourably to approaches that go beyond the initiatives of the day. But any difficulties that were encountered with this project now seem to be in the past and everyone appears to be pulling in the same direction – although the speaker recognised that not all questions can be answered to full technical satisfaction.

Many people have visited the test farm and the programme is likely to be rolled out in Wales, involving as many farmers in the Gower peninsula as wish to participate. It is well recognised that it is the willingness and dedication of the farmer that will determine the effectiveness of the programme. Recognition that herds with repeated skin test failures are a risk to their neighbours may prove to be a significant factor in the programme, and how this comes about is an essential start to understanding disease control options.

The test farm – Gatcombe Farm, ran by Robert and Thomas Reed – is located near Seaton in Devon. The farm is an intensively managed dairy herd with five robot milking parlours and an extensively managed beef herd. The dairy cows stay in their robot group, do not graze and are housed 24/7. Bovine TB has been detected in the dairy cows for years, with repeated failures and over 100 animals slaughtered. The farmer was simply fed up with the time, effort and money involved in having repeat testing with no apparent endpoint. His challenge to his veterinary practice was to control the disease and allow the herd to be managed to maximum benefit without having to keep more animals than wanted because of trading restrictions.

Initial analysis of the testing history showed that only the dairy cows had bTB failures, with no animals from the beef herd failing the skin test. The audience was asked to indicate whether they felt that, within their practice, bTB was being controlled and that the plan to eliminate the disease by 2035 seemed likely. Very few vets raised their hands, but when asked whether they were dissatisfied with progress, there was a forest of arms raised aloft. How many of the vets would be prepared to put in the time and effort needed to help their clients wasn’t asked. More information was awaited by the WCVA members.

The role of badgers

The fact that the beef cows graze the pasture but have no bTB failures was an obvious anomaly and the involvement of badgers was investigated. Setts were located, and dung samples sent to Warwick University, with the finding that M. bovis was present at many locations. Wildlife cameras showed that there was a great deal of badger activity around the woods and pastures but no penetration into the buildings housing the dairy herd. This led to a greater understanding of “infected”, “infectious” and “shedding”.

Analysis of the number of organisms in badger dung and cattle dung, and the volumes of dung excreted, indicated that one shedding bovine will contaminate pasture equivalent to 500 badgers. However, the badgers were a risk factor. Brian May provided funding to vaccinate the badgers; he explained to the audience that his involvement has developed from badger protection to supporting farmers and vets in the control of bTB. If the cattle disease ceases to be an issue, then the badgers will be left alone. He further commented on the intensity of badgers around the maize fields and that dung from the cattle spread on the maize ground encourages worms and grubs, which in turn attracts the badgers. Whatever has been carried by the cattle dung is also available to the badgers. The vaccine is not expected to prevent disease but to reduce the number of animals changing from latency to infectious.

With an understanding from research that inhaled organisms tend to lead to the development of lesions more than ingested mycobacteria, and that radical changes in diet stimulate latent mycobacteria to become active, disease control was targeted on the dairy herd. The dairy herd had shared air space and experienced diet changes throughout the production cycle. Preventing faecal contamination of food and water was identified as a management necessity and cleanliness of the bedding and walkways was an absolute priority.

Testing methods

Examination of the history of past reactors showed that having a bottom lump, regardless of the size of the avian lump, was a factor in subsequent enhanced test failure. Cows with a bottom lump passed further skin tests. Bottom lump cows have also been tested for presence of the organism and antibodies. The findings are not conclusive; the tests are not necessarily validated, but repeated enhanced testing indicates that whatever procedure is adopted, detection of M. bovis varies with time and that no one test, at one time, indicates freedom from disease. Initially, approximately 10 percent of the herd that passed the skin test had bottom lumps and 88 percent of those showed positive to an Actiphage blood test. Comprehensive testing of bottom lump cows continued involving Actiphage, qPCR and IDEXX Elisa.

Those who were concerned about interpretation of the tests remain so, but the speaker explained that only the cows that failed the formal skin test were slaughtered. Other positive test cows were managed so that the risk of disease spread was reduced, utilising Johne’s control principles to prevent new infections from contaminated faeces. Robert Reed pointed out that high risk cows were bred to beef bulls and bedded on straw, which was then composted. Resistance to disease by some animals was briefly mentioned, but that is a major topic for clarification on another day.

Potential for expansion

There are some 67 herds in Devon that have been under restriction for 18 months or more. Veterinary practices are encouraged to identify which of their clients are included. It is expected that the majority will be dairy herds with over 300 cows. It is further anticipated that the farmers will be totally fed up with bTB and could be resistant to yet another initiative. This has not been the case with other herds within the West Ridge Veterinary Practice; of greater concern is the cost of control and the effort required. Robert Reed has received subsidised testing and veterinary time; converting what has been learned on his test farm to more general use will require careful awareness and veterinary support.

Within a few days, over 30,000 comments about the meeting were posted on social media. Such is the impact of involving a musician in disease control. Further conversations have shown that this meeting highlighted a widening expectation between those who are responsible for bTB eradication policy and veterinary surgeons delivering that policy at farm level.