Hypoadrenocorticism is an uncommon endocrine disease in dogs, with a reported prevalence of around 0.06 percent in UK primary-care practice (Schofield et al., 2021); it is rare in cats. Due to its non-specific clinical signs and intermittent nature, it is commonly called “the great pretender”, hinting at the fact that this disease has the potential to go undiagnosed or be misdiagnosed. However, hypoadrenocorticism is of clinical importance due to the potential for progression and presentation as an emergency, with the animal presenting to the clinic in a state of hypoadrenocortical crisis, commonly called an Addisonian crisis.

Physiology of the adrenal glands

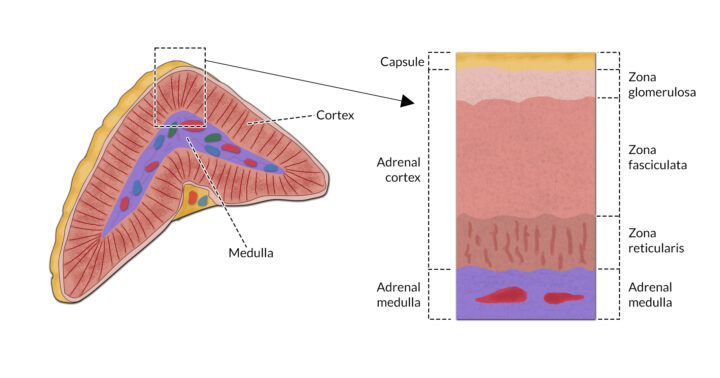

The adrenal glands are paired structures located close to the cranial aspect of each kidney. Each gland consists of an outer cortex and inner medulla (Figure 1). Both layers act independently of each other and are controlled by different mechanisms.

The adrenal cortex is the part of the adrenal gland that is considered essential for life. Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which is released by the anterior pituitary, stimulates the secretion of hormones from the adrenal cortex. These hormones are known as corticosteroids. Around 40 corticosteroids are released from the adrenal cortex, and are classified into three main groups based on their action:

- Glucocorticoids – these regulate all aspects of metabolism (directly and indirectly), cardiovascular function and blood pressure, and play an important role in suppressing inflammatory and immunological responses. The major glucocorticoid is cortisol

- Mineralocorticoids – aldosterone, which helps control excretion of sodium, chloride and potassium in the kidneys, is the most important mineralocorticoid. It is part of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS), and is secreted in response to the presence of angiotensin in the blood due to hypotension

- Sex hormones – these are secreted in small amounts from the adrenal cortex

Catecholamines (adrenaline and noradrenaline) are released from the medulla of the adrenal glands under the influence of the sympathetic nervous system.

Pathophysiology of hypoadrenocorticism

Hypoadrenocorticism, or “Addison’s disease”, is the reduced production of glucocorticoids (cortisol) and mineralocorticoids (aldosterone) by the adrenal glands.

Primary hypoadrenocorticism is the most common cause of hypoadrenocorticism. It involves the immune-mediated destruction of the adrenal gland, which causes the loss of functional adrenal tissue and reduced hormone production (Scott-Moncrieff, 2015). This form is commonly seen in the Standard Poodle, Portuguese Water Dog, West Highland White Terrier and Nova Scotia Duck Tolling Retriever, among others (Hess, 2017). It usually occurs in young to middle-aged dogs, with females typically more affected than males.

Secondary hypoadrenocorticism is less common and occurs as a result of pituitary gland damage, leading to reduced ACTH release. Potential causes include hypophysectomy and pituitary gland neoplasia (Hess, 2017).

Clinical signs

A significant clinical finding in these patients, however, is bradycardia in the face of hypovolaemia

Dogs presenting in hypoadrenocortical crisis are usually collapsed and hypovolaemic with poor pulse quality, pale mucous membranes and increased capillary refill time (Skelly, 2018). A significant clinical finding in these patients, however, is bradycardia in the face of hypovolaemia. Normally, hypovolaemic patients present with tachycardia, but in cases of Addisonian crisis, the presence of hyperkalaemia results in bradycardia. Owners may also report gastrointestinal signs, including vomiting and diarrhoea.

Diagnosing hypoadrenocorticism

Although the clinical signs documented above – particularly bradycardia in the presence of hypovolaemia – are highly suggestive of a hypoadrenocortical crisis, the veterinary surgeon will need to perform diagnostic tests to confirm a diagnosis. Although veterinary nurses do not make the diagnosis, having a good understanding of the required tests and how to interpret their results can increase the efficiency of performing the tests and guide nursing care for these patients.

Haematology is usually unremarkable, which is unusual. In a systemically unwell patient, haematology should reveal a stress leucogram (presence of neutrophilia, lymphopenia and eosinopenia). However, due to the lack of cortisol release in patients with hypoadrenocorticism, they are unable to mount a stress response (Burkitt Creedon, 2015).

Normal electrolyte levels do not exclude the possibility of hypoadrenocorticism because a condition called ‘atypical Addison’s disease’ exists

On serum biochemistry, electrolyte disturbances due to a lack of aldosterone include hyperkalaemia, hypocalcaemia, hyponatraemia and hypochloraemia. A reduced sodium to potassium (Na:K) ratio below 27:1 is also characteristic of hypoadrenocorticism. It is important to note that normal electrolyte levels do not exclude the possibility of hypoadrenocorticism because a condition called “atypical Addison’s disease” exists. Hypoglycaemia may also be documented due to the lack of cortisol which leads to reduced insulin antagonism (Burkitt Creedon, 2015). Azotaemia may also be present.

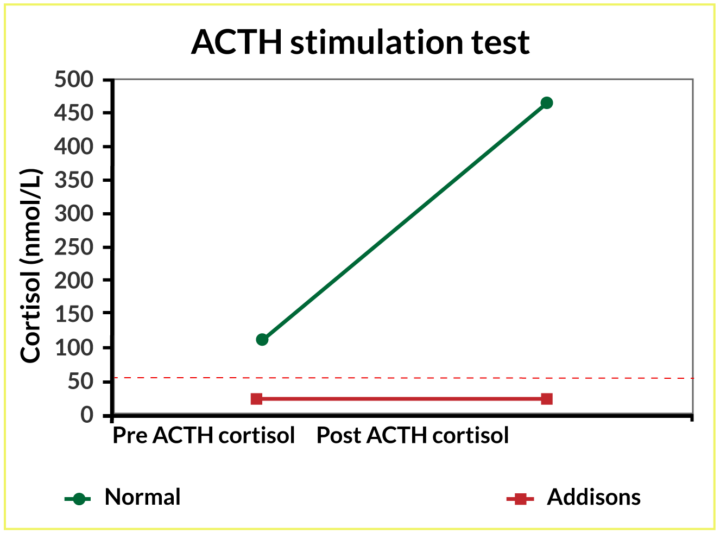

Basal cortisol will be low and can, therefore, be used as a screening test for hypoadrenocorticism. The literature shows that hypoadrenocorticism is unlikely if basal cortisol is above 55nmol/l (Bovens et al., 2014). However, to definitively diagnose hypoadrenocorticism, a complete adrenocorticotropic (ACTH) stimulation test is needed. In a healthy patient, the adrenal gland should release cortisol in response to the stimulation test, a response that would register in the post-ACTH sample. Patients with hypoadrenocorticism are unable to mount this response; no stimulation (release of cortisol) is measurable in the post-ACTH sample (Figure 2).

Due to the presence of hyperkalaemia in these patients and the subsequent bradycardia, an electrocardiogram (ECG) should be performed to determine if a cardiac arrhythmia is present.

Treating the Addisonian crisis

There are four main aims of emergency treatment for the patient experiencing hypoadrenocortical crisis: correcting hypovolaemia, replacing glucocorticoids and mineralocorticoids, addressing hyperkalaemia and providing supportive nursing care.

1. Correcting hypovolaemia

As patients in Addisonian crisis are collapsed and hypovolaemic, they require rapid volume expansion, so a fluid bolus is likely to be administered. In dogs, an initial bolus of 15 to 20ml/kg is given (Pardo et al., 2024). The dog’s vital parameters are then reassessed to determine if further boluses are required.

A balanced isotonic solution such as sodium chloride 0.9% or Hartmann’s is selected for the bolus. There is some debate over fluid choice as Hartmann’s does contain a small amount of potassium and patients with hypoadrenocorticism are hyperkalaemic. However, the positive dilutional effect of the solution will likely outweigh the impact of the small amount of potassium present.

Caution must be taken in dogs with severe hyponatraemia (130 to 140mmol/l) not to increase the serum sodium levels too quickly to avoid life-threatening fluid shifts in the brain

An additional benefit of Hartmann’s is that it has a lower sodium content, as caution must be taken in dogs with severe hyponatraemia (130 to 140mmol/l) not to increase the serum sodium levels too quickly to avoid life-threatening fluid shifts in the brain (Burkitt Creedon, 2015; Pardo et al., 2024).

2. Replacing glucocorticoids and mineralocorticoids

Intravenous steroids can be given to treat the deficiency in glucocorticoids. Administration often leads to a rapid improvement in the patient’s demeanour. If steroids are to be administered before completing the ACTH stimulation test, only dexamethasone (Figure 3) should be used, as all other steroids will impact the results of the test (Scott-Moncrieff, 2015).

Desoxycortone pivalate (DOCP), available under the trade name “Zycortal”, is an injectable mineralocorticoid replacement. Once started, fluid balance and electrolyte levels must be carefully monitored to ensure sodium levels do not rise too rapidly.

3. Addressing hyperkalaemia

Patients with hyperkalaemia may respond to intravenous fluid therapy (IVFT) alone, but severely hyperkalaemic patients with significant bradycardia which does not improve with IVFT require additional therapy to protect the heart.

Calcium gluconate 10% (Figure 4), administered by slow constant-rate infusion (CRI), can be used as a cardioprotective measure. Although this will not reduce the circulating levels of potassium (so the patient remains hyperkalaemic), it will raise the cardiac threshold potential, protecting the heart from the effects of hyperkalaemia. The hyperkalaemia will, however, still need to be addressed. One important consideration when administering calcium gluconate by CRI is to ensure an ECG is attached and monitored due to the risk of worsening the bradycardia.

Another option that will reduce circulating levels of potassium is to administer neutral (soluble) insulin. The insulin works by “unlocking” the cells in the body, allowing the potassium to enter the cells and reducing the extracellular (circulating) levels. Due to the subsequent hypoglycaemia resulting from insulin administration, blood glucose must be monitored and dextrose supplemented if required.

4. Providing supportive nursing care

Patients with hypoadrenocorticism may require intensive nursing care during the initial emergency period

Patients with hypoadrenocorticism may require intensive nursing care during the initial emergency period. Interventions during this period can include recumbent nursing care such as regular turning, oral care and plenty of padded bedding.

Close monitoring of cardiovascular parameters is required to monitor not only the response to treatment but also for deterioration. The dog will likely receive several fluid boluses, and monitoring for signs of fluid overload (tachypnoea/dyspnoea, weight gain, oedema) is crucial.

Depending on the patient’s presentation and demeanour, an indwelling urinary catheter (IDUC) may be considered to manage the bladder and avoid discomfort and/or soiling. This device also allows for the accurate monitoring of urine output, which helps guide the IVFT plan. However, IDUC placement is not a benign procedure and comes with its own risks, including the potential introduction of bacteria resulting in urinary tract infection. Therefore, the benefits must be compared to and outweigh the risks.

Nutrition is an aspect of patient care that is often and easily forgotten when dealing with emergencies as the focus tends to be on treating the more immediate, life-threatening issues

Nutrition is an aspect of patient care that is often and easily forgotten when dealing with emergencies as the focus tends to be on treating the more immediate, life-threatening issues. However, it is an area where veterinary nurses can be proactive: calculating the patient’s resting energy requirement, ensuring they fulfil this and alerting the veterinary surgeon in a timely manner if they are not meeting it. Poor nutrition can lead to many complications, including reduced immune defence, so appropriate support should be implemented as soon as possible if needed.

Long-term management of hypoadrenocorticism

In the long term, dogs will be transitioned to a medical management plan that includes mineralocorticoid (DOCP or fludrocortisone) and glucocorticoid (prednisolone) supplements. This treatment will be lifelong, but the dosage is usually tapered based on clinical response and bloodwork monitoring.

Owners should be counselled on the importance of medication and the consequences of not sticking to a regime. Clear guidance and information should be provided (orally and written) regarding the signs to monitor which may indicate deterioration in their pet’s condition. It is also crucial to listen to the owners if they are concerned that their pet is “not quite right” – remember the signs of the disease are subtle and so any deterioration in their condition can be as subtle.