Endoscopic examination of the lower urinary tract – referred to as cystoscopy – is performed in dogs with a variety of urinary tract issues. It is performed less commonly than other endoscopic procedures, for example, gastrointestinal endoscopy and bronchoscopy.

Cystoscopy allows for evaluation of the vagina, urethral opening, urethra, urinary bladder and ureteral openings. The procedure can allow for diagnosis of ectopic ureters, biopsy sample collection and urolith retrieval where indicated. Some minimally invasive procedures can also be performed with the correct equipment and training, including laser lithotripsy of uroliths (breaking uroliths down into smaller pieces which can be excreted) and laser ablation of ectopic ureters.

Cystoscopy is not commonly performed in cats due to their small size. Even though cystoscopes are the narrowest scope available, they are still too large for most feline urethras.

Indications and contraindications

There are several indications and contraindications for cystoscopy as shown in Table 1.

| Indications | Contraindictations |

| Persistent haematuria (once a bleeding disorder has been excluded) | Patient not stable for general anaesthesia |

| Dysuria/stranguria/tenesmus | Thrombocytopenia or coagulopathy |

| Pollakiuria | Ruptured urinary bladder/urethra |

| Recurrent and chronic urinary tract infection | Complete urethral obstruction |

| Urinary calculi | Recent urethrostomy or cystotomy (less than seven days) |

| Urinary incontinence | |

| Abnormal imaging findings (eg suspicion of polyps) | |

| Neoplastic cells in urine sample |

Alongside the specific contraindications listed, limitations to the use of cystoscopy include small patient size and a lack of instrumentation and expertise. Cystoscopy may form part of the work-up in cases with haematuria, once a bleeding disorder has been ruled out as the cause (Figure 1).

Equipment for cystoscopy

The lower urinary tract is a sterile environment and, due to the procedure being performed, there is a risk of introducing contaminants and causing iatrogenic urinary tract infection. With this in mind, it is important to ensure that equipment is sterile and the environment is clean.

Equipment required for cystoscopy includes:

- Endoscope of appropriate size and rigidity: a rigid endoscope is used for female dogs (Figure 2), while a small flexible endoscope is used in male dogs

- Instrumentation: for example, biopsy forceps or basket foreign body retrieval forceps

- Bag of sterile saline in a pressure bag connected to a giving set

- Sterile 50ml syringe and three-way tap

- Sterile gloves for the endoscopist and assistant

Patient preparation

All patients undergoing cystoscopy should be prepared for anaesthesia following the individual practice’s protocol.

A full pre-anaesthetic assessment should be performed, and an individual anaesthetic plan developed by the anaesthetic team. An opioid may be administered as part of the premedication; although the procedure itself may not be painful, it may be uncomfortable, and the veterinary surgeon may decide to take biopsy samples.

All patients undergoing cystoscopy should be prepared for anaesthesia following the individual practice’s protocol

Patient positioning depends partly on the veterinary surgeon’s preference, but male dogs are always placed into lateral recumbency with the veterinary surgeon standing to the side of the table to be able to access the penis. Bitches can be placed either in ventrodorsal recumbency or in lateral recumbency with the hind end as close to the table edge as possible and the legs pulled slightly forward. The veterinary surgeon will stand at the end of the table for access.

Once the patient is in a suitable position, the site should be prepared. Fur around the prepuce or vulva should be clipped; this should be done carefully to avoid causing irritation. The site should be surgically prepared. The tail of female dogs is wrapped with a bandage to prevent it from becoming wet or soiled.

Procedure

Once the patient is anaesthetised and prepped, the endoscopist can insert the cystoscope. In the female, this would be into the vagina and then the urethra followed by the bladder. In the male, it would be directly into the urethra, after extrusion of the penis by an assistant, followed by the bladder. All areas are examined as the scope is passed for evidence of inflammation, masses or strictures.

After the endoscope has been passed through the urethra and is in the bladder, the assistant can empty the bladder of urine using the 50ml syringe and three-way tap. Once emptied, the sterile saline is attached to either the instrument channel of a flexible scope or the working sheath of a rigid scope by the giving set. The bladder is filled with this saline, which improves visualisation, allowing more thorough examination of the bladder.

Once within the bladder, the endoscopist will spend time observing the bilateral ureteral openings. They will establish that the ureters enter the bladder in the correct places (at the level of the trigone) to ensure the patient does not have ectopic ureters, and will confirm visualisation of urine jets exiting both ureters.

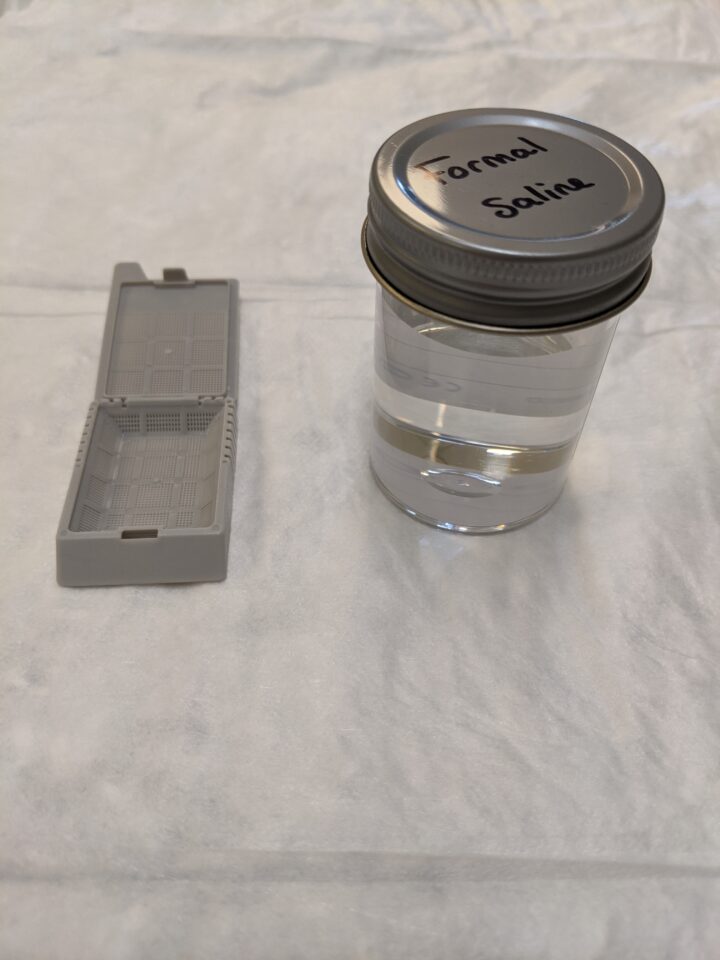

If deemed necessary, biopsy samples can be collected once the endoscopist has finished examining the urethra and bladder (and vagina in the female dog). Usually, several biopsies are collected and may be taken from different areas. It is important to ensure that the sample pots are correctly labelled with the area of sampling. Samples for histopathology are stored in biopsy cassettes and formal saline (Figure 3), while a biopsy for culture and sensitivity should be stored in a 1ml plain blood tube with sterile saline.

The endoscopist can also perform any additional procedures that are required, for example laser lithotripsy; however, discussion of this is outside the scope of this article.

Supporting the patient in recovery

Following cystoscopy, the patient should be monitored closely until they are fully recovered from anaesthesia. Oxygen delivery should continue until the patient is extubated, and continued longer by other means of delivery if the patient’s condition requires it.

Standard post-anaesthetic monitoring includes (Grubb et al., 2020):

- Measurement of vital signs (heart rate, respiratory rate, temperature)

- Mucous membrane colour and capillary refill time

- Blood pressure

- Pulse oximetry if tolerated

It is important not only to measure urine output volumes but also to monitor for any changes to urination, for example dysuria or stranguria

Regular pain assessments should be performed, and appropriate analgesia administered under the instruction of the veterinary surgeon. To aid in comfort, the veterinary surgeon should empty the bladder of saline before recovery, and the bladder should be palpated to ensure it is empty.

Urination post-cystoscopy should be monitored. It is important not only to measure urine output volumes but also to monitor for any changes to urination, for example dysuria or stranguria. Normal urine output in dogs is to 1 to 2ml/kg/hour. It is important to be aware of the patient history to understand if these clinical signs are pre-existing or new and potentially related to the cystoscopy.